Manage Containers With Cockpit and Podman

As a DevOps Enginerd, I’m keen to work with developers, helping them onboard their applications to CI/CD pipelines. If you’re wondering, a CI/CD pipeline is essentially multiple automations linked together so that a git commit -m "I changed all the things" results in a change to a live application (following the good ole’ DEV/TEST/PRE-PROD/PROD pathway of course!). Unfortunately, there is often a gap between being able to run an application on a laptop and onboarding it to an enterprise-grade CI/CD pipeline, mostly because so many things can go wrong. Admittedly, containerizing an application isn’t particularly new in 2023, but adding the combined power of Cockpit and Podman to a development toolchain adds some nifty functionality - helping to bridge the gap by adding the ability to graphically manage (and even create) containers on individual servers, proving an app works without entering the morass that can be onboarding to a CI/CD pipeline.

What is Cockpit?#

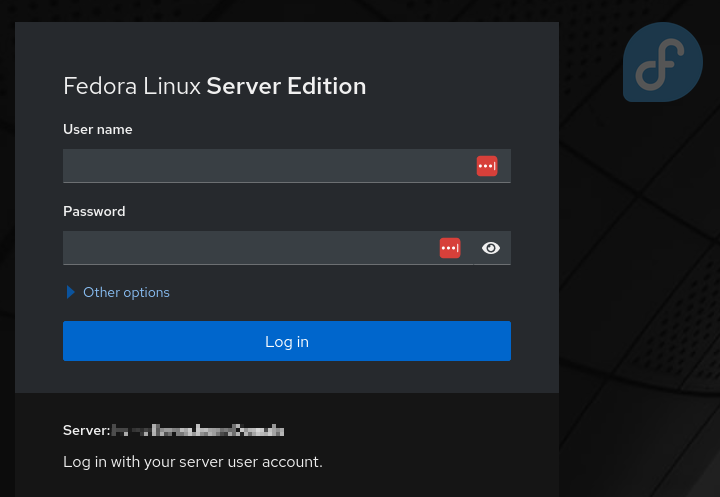

Cockpit is a graphical way to administer a Linux server - a service available by default in all RHEL family distributions (Fedora/CentOS/RHEL/Rocky/Alma) and also on many other distributions (see Cockpit Project for more details). The default (but configurable) port is 9090, so simply accessing <serverIP>:9090 in a browser results in a nice login screen:

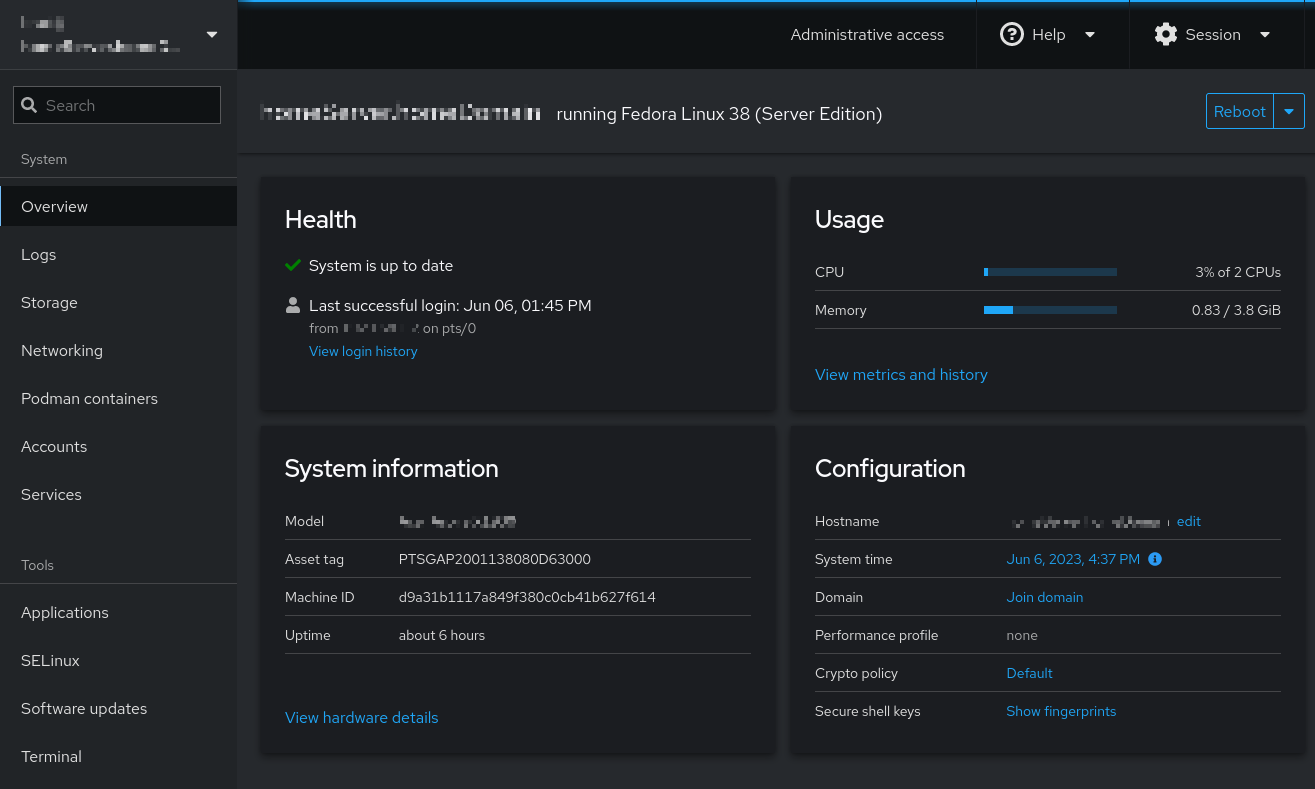

And then, naturally, Cockpit’s GUI presents many options:

Cockpit is very powerful - and can be used by everyone - beginning system administrators and experts alike. Of course, large enterprises often use monitoring tools like a combination of Prometheus and Grafana to observe their entire infrastructure - but viewing the CPU/RAM, storage, network, and software services of an individual server provides great observability. As you’ll see below, Cockpit is a systemd service, but it runs on a socket so it is only activated when someone is actually using the browser - thereby being very light on resources.

In a home lab, Cockpit is amazing - it does just about everything that a power-user could ask for - allowing you to have remote control over a Linux server hosting as many containers/services as you’d like, all visible from any device with a screen (yes, I use my phone to manage my home server because I can).

Installing Cockpit#

Depending on your distribution, Cockpit may already be installed. If not:

sudo dnf install cockpit # RHEL Family

sudo apt install cockpit # Debian Family

Enable the socket:

sudo systemctl enable --now cockpit.socket

To open the firewall ports (if needed), execute the following commands:

sudo firewall-cmd --add-service=cockpit --permanent

sudo firewall-cmd --reload

What is Podman?#

Podman (Pod Manager) is an alternative to Docker within Linux, associated mostly with the RHEL family but also available in other distributions. Podman.io has tons of information (some of it very technical!) but in a nutshell it has at least the same if not better functionality than Docker (the underlying mechanism is more Linux-kernel friendly). Even better, it is engineered to be command-compatible, so docker run -d -p 80:80 nginx and podman run -d -p 80:80 nginx yield the same results (all else being equal!).

While I find Docker and Podman largely interchangeable, Podman does have the huge advantage of being able to run rootless containers. This means that containers can run without root permissions, and can even run based on a regular user ID even though that user is not logged in (once configured correctly). This means that servers, with all their extra horsepower and network connectivity, can host containers that are controlled by developers, not system administrators (or DevOps Enginerds like me). So a developer can containerize their application, test its basic functionality and connectivity to the larger ecosystem, all without venturing into the complexity of a CI/CD toolchain, until they’re sure the application works as expected. No more onboarding apps only to find that they don’t do half of the things that were in the requirements.

Managing Podman Containers in Cockpit#

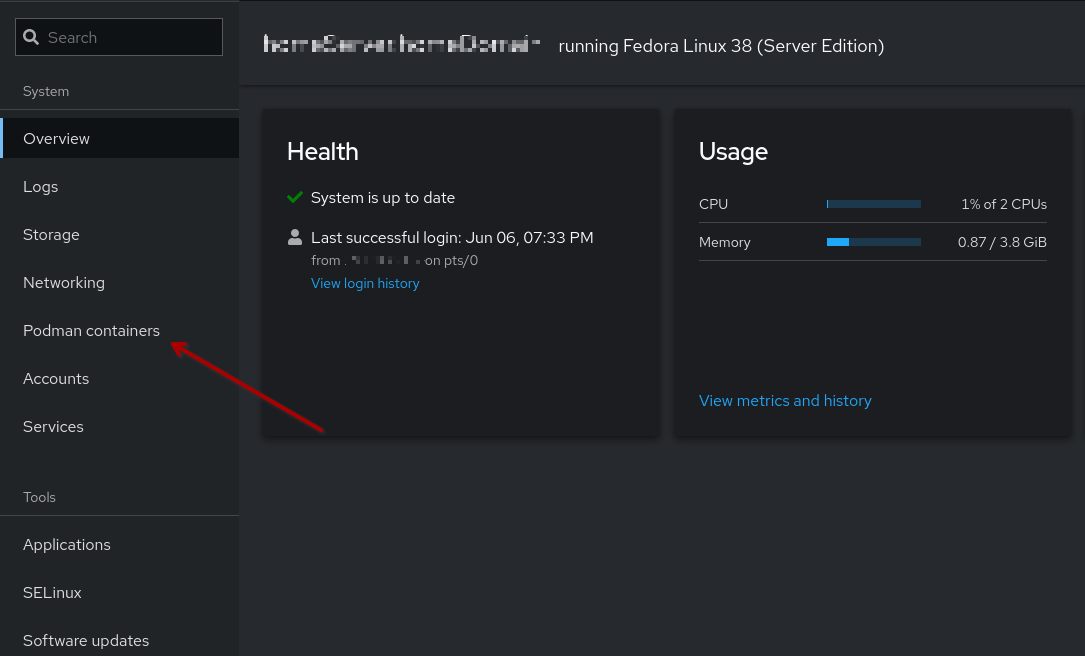

So how do Cockpit and Podman work together? Amazingly - once you’ve installed the software. Assuming Cockpit is already up and running, simply run dnf install cockpit-podman (even while Cockpit is running) and suddenly you’ll see a new menu item appear:

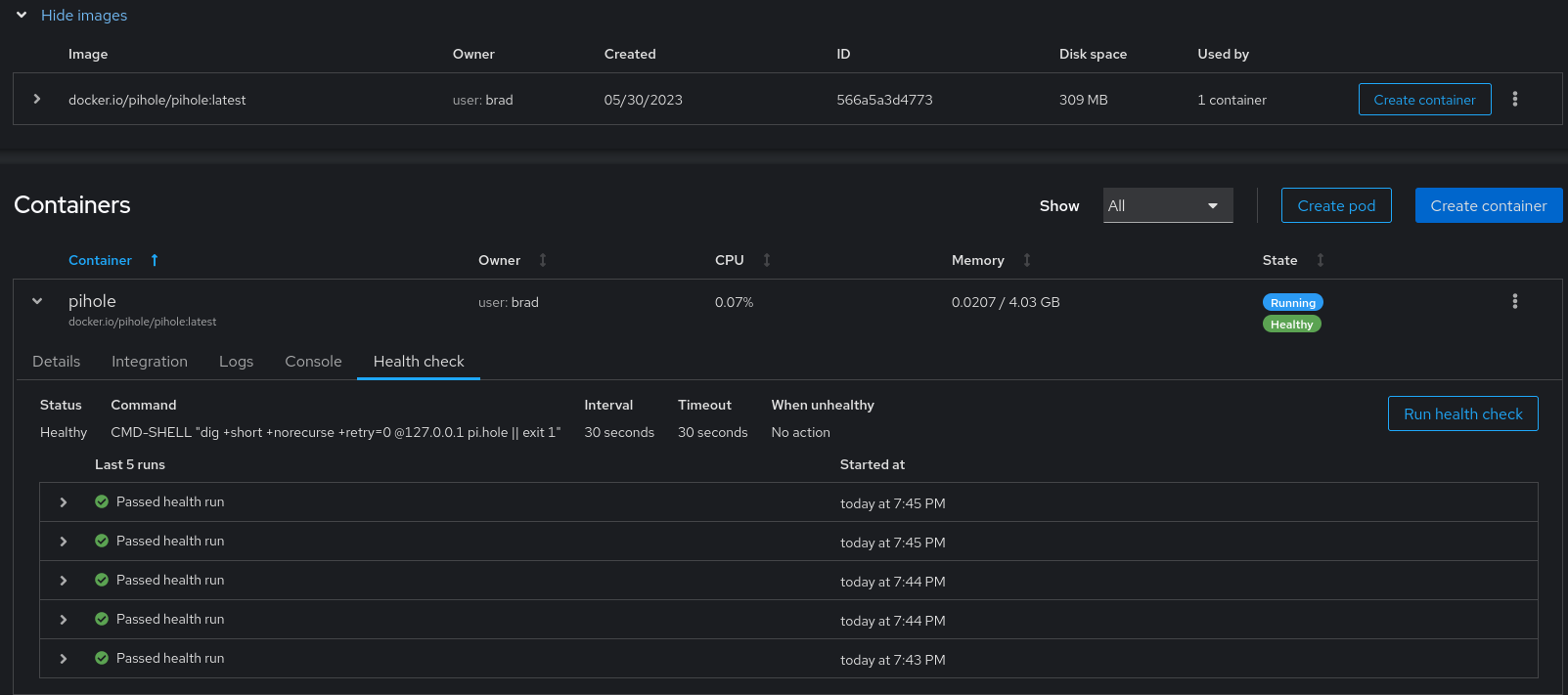

That menu gives you the ability to see a container as it is running, and even shows you the health checks that the podman service is running on your container on a regular basis:

As you can see above, I’ve spun up an instance of PiHole based on Running pi-hole as a podman container in Fedora to protect my home network from ads - that’s a story for another time!

So with this power, a developer can use Cockpit to monitor the system resources that their container is using, check its health, compare its performance to the performance of the server, and validate that their app works as expected and connects to all the other dependencies as it should. A whole world of possibilities open up, all with a GUI to guide both beginners and experts. It is even possible to create Podman containers in Cockpit, but realistically this will most likely still be done via command line due to the anticipated complexity of most containers.

That’s Nice, But Why Would I Use This?#

In a nutshell - because onboarding to CI/CD pipelines is hard. My style of work is to take one baby-step at a time, ensuring what is behind me is solid and ready for the next step. I loathe situations where something is broken and there are 496 things it could be, because we changed 496 things since the last time we tried to run this. Change one thing at a time, and make sure that whatever was changed works, before changing the next thing.

As I mentioned above, I feel that this Cockpit/Podman duo bridges the gap between “it runs on my machine” and “its in a Prod pipeline”. As much as we’d all like to be building purely cloud-native apps, the fact of the matter is, A LOT OF enterprise-grade computing is not yet cloud-native. There is still tons of local development happening, and the struggle between a git commit and a full-blown “app-in-a-CI/CD-pipeline” is often a drawn out and painful exercise for everyone involved in creating software. The ability to test containerization on a real server and work with a GUI to see the health of both the server and the container might make that pain go away, or at least make it easier to manage.